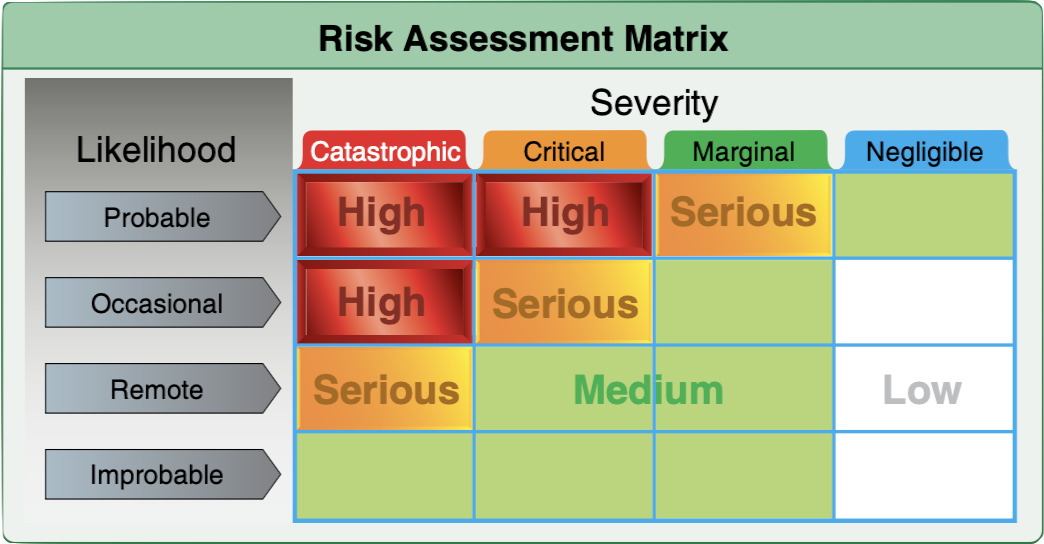

I wrote in my last post that flying involves uncertainty. Good decision-making depends on a realistic look at the likelihood of possible outcomes weighed against their potential severity. Yet a good decision could still end with a bad outcome. And a good outcome can happen despite a bad decision. Why is that? Annie Duke says two factors determine how things turn out: “the quality of our decisions and luck.”[1]

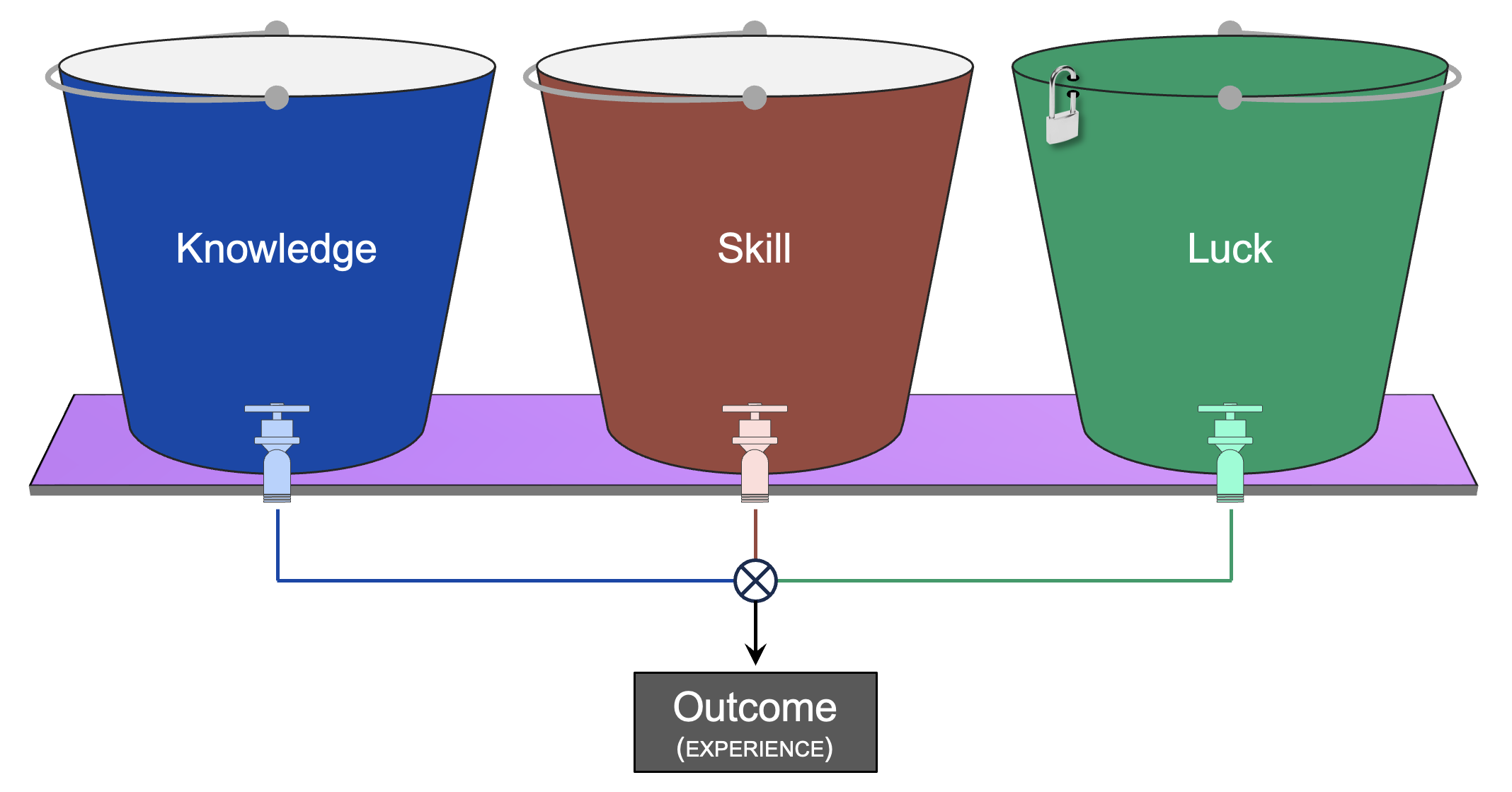

It’s said we bring metaphorical buckets to flying. I like the Navy’s version, which proposes three buckets.[2] I’ve adapted that version to my way of thinking.

In my mind, one of the buckets symbolizes knowledge. Another symbolizes skill. Knowledge about a domain doesn’t always confer competence in that domain.[3] For instance, someone might be good at baseball analytics, but terrible at catching fly balls. Likewise, it’s one thing to describe how to land in a crosswind, but another to be able to do it. You need skill for the latter. And you build skill through “repetitiveness and consistent effort.”[4]

Our aviation knowledge and skill buckets start out almost empty. They will hold whatever amount of knowledge and skill we put into them. And they will never overflow. The fuller these buckets, the better our decision making. But since the buckets are open, unused knowledge and skill can evaporate over time. Hence, the need for continuing education and practice.

The third bucket? That represents luck. Unlike the other two, your luck bucket starts out full. But it’s also sealed and cannot be refilled. What you use, you lose. Best to draw from it sparingly.

The outcome of any situation is a combination of knowledge, skill, and luck. Reflecting on the whole experience will feed back into your knowledge and skill buckets.

The goal is to fill your knowledge and skill buckets before your luck bucket is empty. Most of us have had to draw from our luck buckets during our flying careers. Have you ever said, “I won’t do that again”? If so, I bet it was because of an eye-opening experience. An experience that got funneled right back into your knowledge bucket. It’s also a good bet the spigot on your luck bucket was open. Hopefully not wide open. Unless the situation was heading toward a bad outcome despite your good decision-making.

ICAO defines competency as the “combination of skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to perform a task to the prescribed standard.”[5] Flight time alone is a poor indicator of competence. Context matters. What’s inside those flight hours? What relevance do those hours have to the specific type of flying?

Examples of core competencies include things like flight path management and problem solving. An indicator of the former is controlling the airplane “with accuracy and smoothness.”[6] Of the latter, seeking “accurate and adequate information.”[7] Here are the four levels of competence:

“You never know on which flight you will be judged.” Robert L. Sumwalt [8]

We can make connections between the levels of competence and the bucket metaphor. For example, we’d expect those at the incompetent levels to be more reliant on luck for good outcomes. The consciously competent might need a shot of luck if things don’t go exactly as planned. The unconsciously competent, on the other hand, rely on their knowledge and skill. Luck might come into play only under extraordinary circumstances.

Fly long enough and you’ll run into pilots who don’t realize that their performance is poor.[9] Overconfidence, fixed mindsets, and hazardous attitudes often blind them to their incompetence.

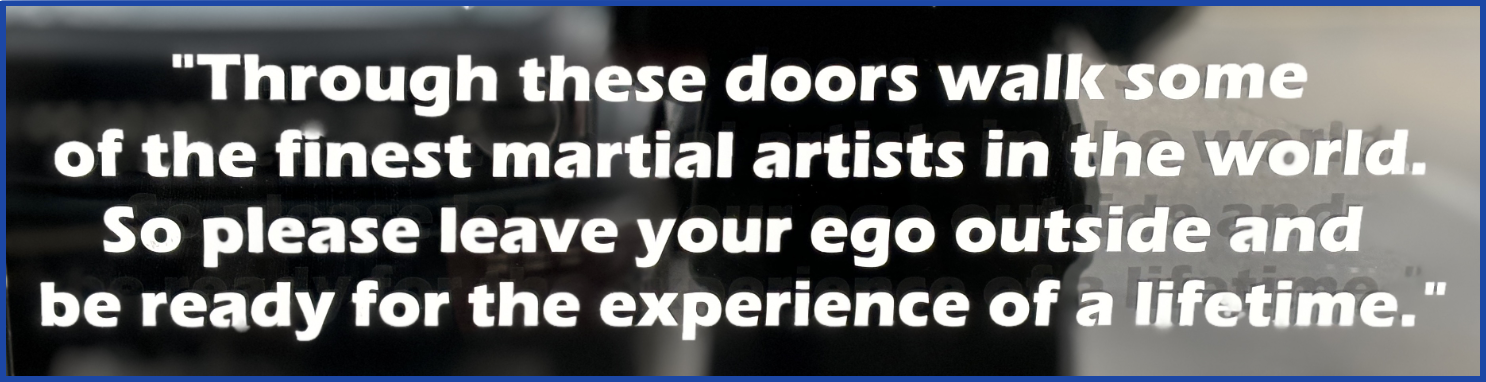

In Left of Bang, the authors note that “[l]earning is impossible without humility.”[10] Also, enthusiasm is one thing. Cockiness is another. Steer clear of the self-proclaimed ace-of-the-base. Hang with those who are always learning instead.

One of my favorite trainees says, “I’m coachable.” This from a retired NFL lineman with a Super Bowl ring. Someone who served in the Army National Guard as a helicopter crew chief. A lifelong learner.

The wording at the entrance to our Krav Maga studio establishes a culture of humility. We’re quizzed on it every so often. What if FBOs everywhere had a similar sign on their doors?

Flying light airplanes is riskier than the routine activities of daily life. Further, pilot error triggers most aviation accidents. So, we need to be honest about our abilities. After assessing risk, ask yourself how much money you’d be willing to bet on the outcome. That might show how much faith you’re putting in luck.

Even better, would you bet your life on it?

——

[1] Annie Duke, Thinking in Bets (Portfolio/Penguin, 2019), 4.

[2] See CDR Steven Baxter, USN, “Three buckets of naval aviation,” The Free Library, S.v., retrieved Jan 8, 2024 from https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Three+buckets+of+naval+aviation%3a+this+old+guy+obviously+had+been+to...-a082064031; and Capt. Carl Meuser, U.S. Navy (Ret.), “The Three Buckets,” Proceedings, Vol.146/3/1,405 (March 2020).

[3] Justin Kruger and David Dunning, “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments,” Psychology, 2009, 1, 44.

[4] Jose Ruiz, “The Differences Among Knowledge, Skills and Experience,” Forbes, March 31, 2021, Retrieved December 15, 2023, https://www.forbes.com.

[5] International Civil Aviation Organization, Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training, Doc 10011, First Edition 2014, xi.

[6] Ibid., A-4.

[7] Ibid., A-6.

[8] Robert L. Sumwalt, NTSB Vice Chair, “Professionalism in Aviation,” Spring Aviation Safety Seminar, UND, March 30, 2011, Slide 45.

[9] Kruger and Dunning, “Unskilled and Unaware of It,” 43.

[10] Patrick Van Horn and Jason A. Riley, Left of Bang, (Black Irish Entertainment LLC, June 2014), 200.

>> This post was written by a human <<

Sign up to receive an email whenever Rich Stowell publishes content