Growing up, the Wright brothers were encouraged “to pursue intellectual interests, to investigate whatever aroused curiosity.”[1] That coupled with the process of designing and flying the world’s first controllable airplane likely informed their approach to training other pilots. When the Wrights opened their flight school in Dayton in 1910, the program had three parts: ground instruction, simulator training, and flight training.[2]

The Wrights’ program had the earmarks of an optimal learning experience. Research into human performance later showed that they were on the right track. Unfortunately, civilian pilot training went in a different direction. By 1944, typical flight training centered on “a theory of building the airplane rather than of flying it.”[3] Worse, some flight schools make pilots to do all their learning in the airplane. And sometimes without the benefit of a training syllabus.

Learning to fly has been treated as if it’s different from learning to do other things. But like many sports, flying involves a complex set of physical and mental skills. Peak performance requires us to develop good coordination between our hands, eyes, and feet. It also requires us to manage our mind, body, and emotions in a dynamic environment.

Sports training methods, psychology, and equipment have evolved over the years. As a result, modern athletes are performing better younger. What about training methods in general aviation? Are we seeing better stick and rudder skills at the private pilot level now compared to the past? Top instructors and designated examiners don’t think so. How else to explain that one-in-four pilots believe the rudder turns an airplane?[4] Or that inflight loss of control remains the number one fatal accident category in general aviation? Or that nearly 85 percent of aviation accidents over the last two decades were caused by pilot error?[5]

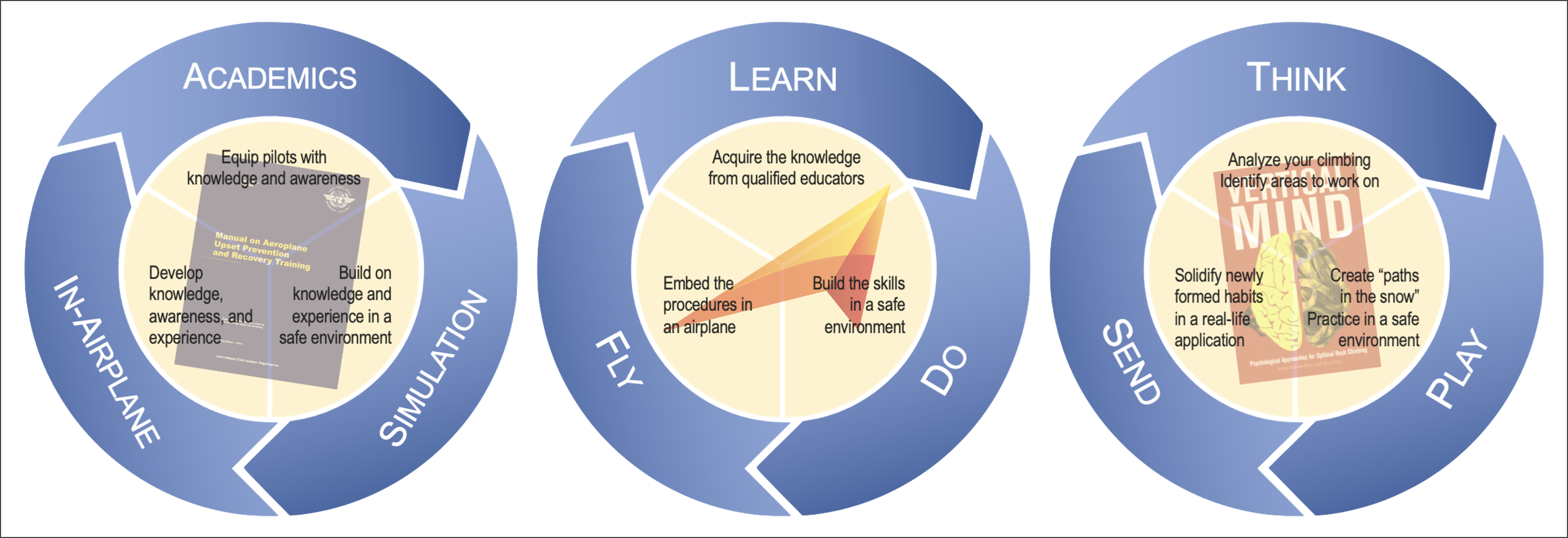

In 2014, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) released its “Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training.” An effective upset training program must include academic, simulator, and in-airplane training.[6] Community Aviation’s version is Learn-Do-Fly.

Not surprising, training routines in sports that demand peak performance follow a similar pattern. The framework for optimal rock climbing, for instance, is Think-Play-Send.

The graphic compares the ICAO, Community Aviation, and rock climbing frameworks. Different contexts, but the same idea. An idea that’s over 100 years old.

Let's look at Community Aviation's framework.

This is where the flight plan is developed. What background knowledge do I need? What am I going to do? What are the objectives? How will I execute the plan? What are the common errors? The tips, the tricks? How does this relate to other flying activities? What will I do if something goes wrong? Details please!

Have you seen downhill skiers swaying as they visualize the course before their runs? Aerobatic pilots hand flying their maneuvers before climbing into their airplanes? Watch how the Blue Angles use mental imagery to rehearse before a practice flight:

Do is where you simulate like an elite athlete or a Blue Angel. It can be as simple as mental practice at home. Running through procedures on a desktop flight simulator. Training in a motion simulator. You can make and learn from mistakes here with little risk of harm. As important, this step can improve your in-airplane performance.

Visualization helped retired Thunderbird pilot Michelle “Mace” Curran perform better. READ. “What was make or break for my success was a form of preparation known as chair flying…. visualizing every detail of a flight…. mentally flying the sortie over and over allowed me to move from the slow, awkward stage…to developing habit patterns.”[7]

It’s now time to fly the airplane. Time to embed the knowledge, procedures, and techniques in the flight environment. The question is, “how should I divide my time between learning, doing, and flying?”

On average, spend more time learning and doing than flying. Rod Machado suggests that the ratio of ground-to-flight training time should be two-to-one.[8] Research found a mix of 75 percent mental and 25 percent physical training to be “more effective than 100 percent physical training.”[9] That’s a ratio of three-to-one once you have the correct mental model in place. Every flight, especially instructional flights, should be briefed and debriefed.

As noted in an earlier post [Knuckleballers], the more developed your stick and rudder skills, the more mental energy you can devote to other tasks. Over-learning the basics also reduces “the likelihood that performance will be interfered with by anxiety and/or emotional arousal.”[10] So integrate learning, doing, and flying into your training routine.

Flying skills are perishable. Keep working through the parts of the learning cycle, refine what you’ve learned, and repeat. Have a growth mindset. Review and rehearse often. Challenge yourself to practice at least one skill on every flight. And above all, make it fun!

[1] Paul K. McCutcheon and William E. Baxter, “Taking to the Skies: The Wright Brothers and the Birth of Aviation,” Smithsonian Libraries, December 2003, available https://www.sil.si.edu/ondisplay/flight/intro.htm

[2] The simulator was a Flyer “with control levers connected to an electric motor that controlled the wing warping.” Dennis Parks, “Flight training the Wright way,” General Aviation News, March 8, 2015, available https://generalaviationnews.com/2015/03/08/flight-training-the-wright-way/

[3] Wolfgang Langewiesche, Stick and Rudder, 1944, 5.

[4] Results of surveys of almost 900 pilots taken during several presentations I gave.

[5] FAA, “Risk Management Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-2A, 2022, ii.

[6] ICAO, “Manual on Aeroplane Upset Prevention and Recovery Training,” Doc 10011 AN/506, First Edition 2014, 2-1–2-2.

[7] Michelle “Mace” Curran, “Drinking from a Firehose,” Inverting Your Mindset, LinkedIn, March 10, 2023, available https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/drinking-from-firehose-michelle-mace-curran/?trackingId=VeWReLe0ROysstJy6VMVZA%3D%3D.

[8] Rod Machado, Rod Machado’s Private Pilot Flight Training Syllabus, 2018, 47, available for free at https://rodmachado.com/collections/flight-instructor-collection.

[9] Fred G. DeLacerda, Ph.D., Peak Performance for Aerobatics, Iowa State University Press, 2002, 49.

[10] Robert M. Nideffer, Ph.D. (n.d.), Getting Into The Optimal Performance State.

>> This post was written by a human <<

Sign up to receive an email whenever Rich Stowell publishes content