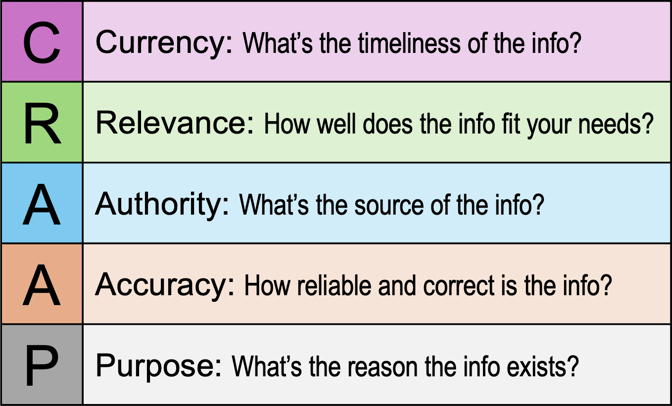

Private pilot flight training material alone can fill a home library. But how current is that information? How relevant is it to flying an airplane? Who’s the authority? Is the information accurate? What is its purpose? This is the CRAAP test. It’s a way “to evaluate the nature and value” of information.[1]

In this case, consider the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as the authority. The FAA has been doing a good job of keeping their handbooks current. The Airplane Flying Handbook, for instance, was updated in 2016 and again in 2021. The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, 2016 and 2023. The Aviation Instructor’s Handbook, 2008 and 2020.

Get the Latest FAA Handbooks & Manuals Here

Let’s gage the relevance of some of the content.

Some concepts stand the test of time. For example, Captain H. Barber wrote: “learn to fly as if to the instinct born so that one may give practically all one’s attention to other things than merely flying the machine.”[2] That was in 1918.

A century later, the Aviation Instructor’s Handbook restates it like this: “the ability to instinctively perform certain maneuvers or tasks that require manual dexterity and precision…. allows the pilot more time to concentrate on other essential duties.”[3]

In 1957, Major Harley Barnhart wrote: “the underlying purpose of flight training must be to develop skills and safe habits that are transferrable to any aircraft.”[4]

Sixty-four years later, the Airplane Flying Handbook says: “The purpose of flight training is to develop the knowledge, experience, skills, and safe habits that establish a foundation and are transferable to any airplane.”[5]

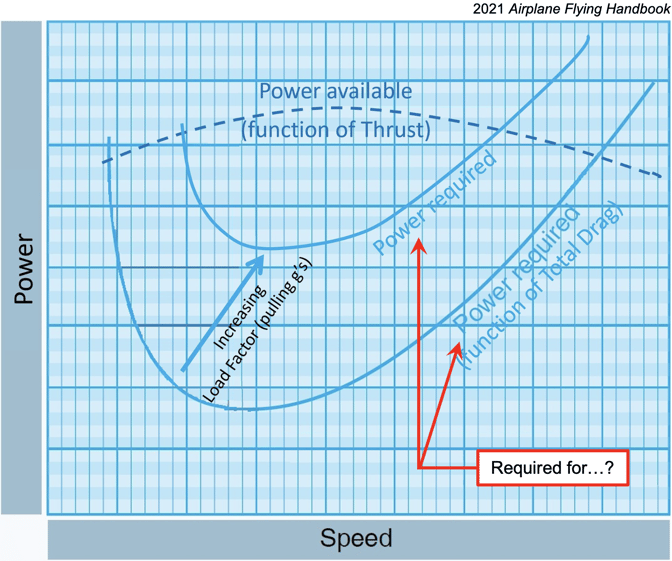

Relevant information might also be assumed or edited out of the handbooks. For example, “power required” appears 17 times in the FAA’s new “Energy Management” chapter.[6]

Does everyone know what the power is required for? Why not say it’s the power required for steady, level flight? At least once. Several times would be better. Especially in a chapter about energy management. Such information would also give needed insight into the roles of pitch and power.

Flight training should focus on what we need to know to fly in three dimensions. The 1951 Flight Instruction Manual, for instance, described the chandelle as “part of a loop in an oblique plane.”[7] Learning to visualize maneuvers in the horizontal, oblique, and vertical improves spatial awareness. Military and aerobatic pilots learn to do this. Yet the word “oblique” vanished in later Airplane Flying Handbooks.[8] The word “horizontal” now refers mostly to a component of lift or parts of the airplane. And “loop” is mainly used in the context of ground loops.

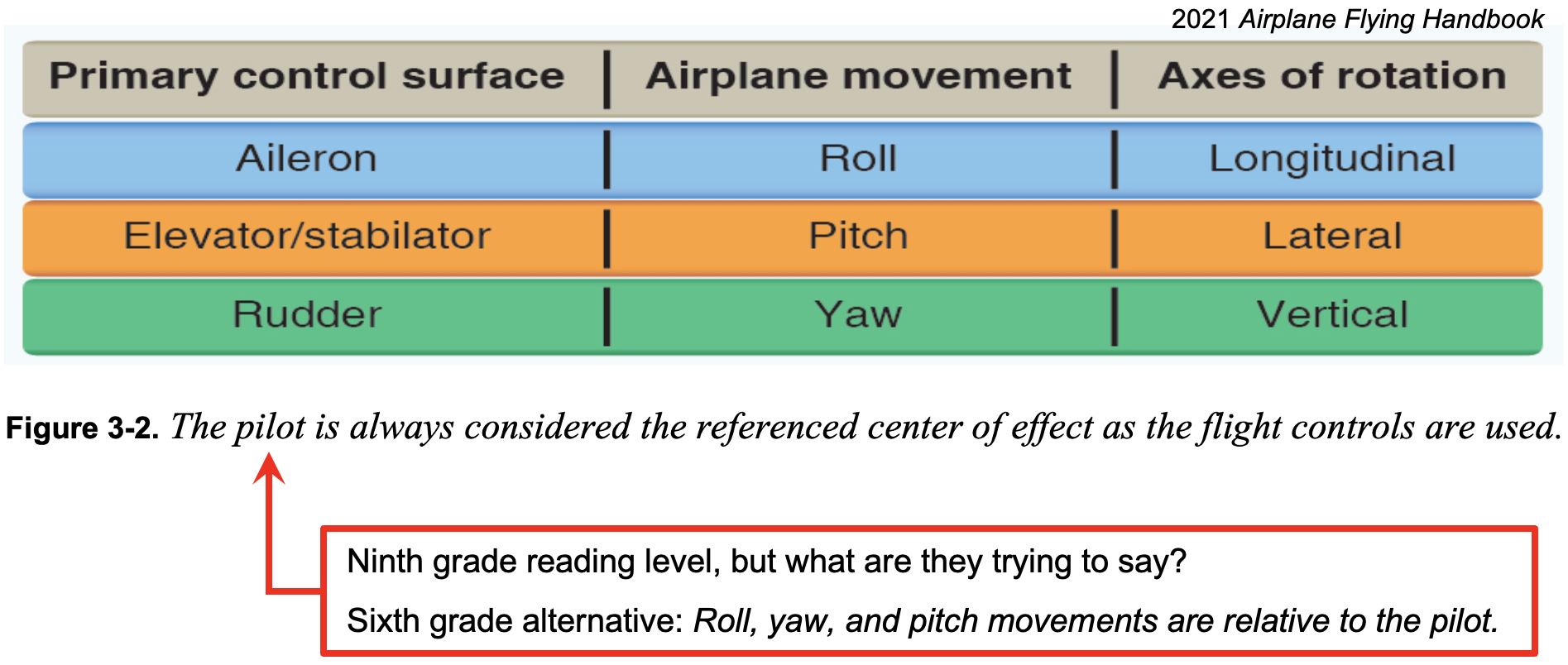

Borrowing language I’ve used since 1987, the Airplane Flying Handbook now describes roll, yaw, and pitch motions relative to the pilot’s body.[9] And only in one place. But what’s vital for you to know to control your airplane? To fly safely, confidently?

Is it memorizing the phrase “horizontal component of lift,” which is mentioned 18 times? Or developing the ability to sense roll, yaw, and pitch no matter the airplane’s attitude? Realizing that “lift” must be important because it’s referenced over 180 times? Or being able to make appropriate roll, yaw, and pitch inputs no matter the airplane’s attitude?

Roll, yaw, and pitch make up one of the nine principles of light airplane flying. Their relevance to controlled flight cannot be overstated. It’s one thing to paste words into a handbook. It’s another to show how the concepts conveyed by the words apply to various maneuvers. Making those connections moves you to the correlation level of learning.

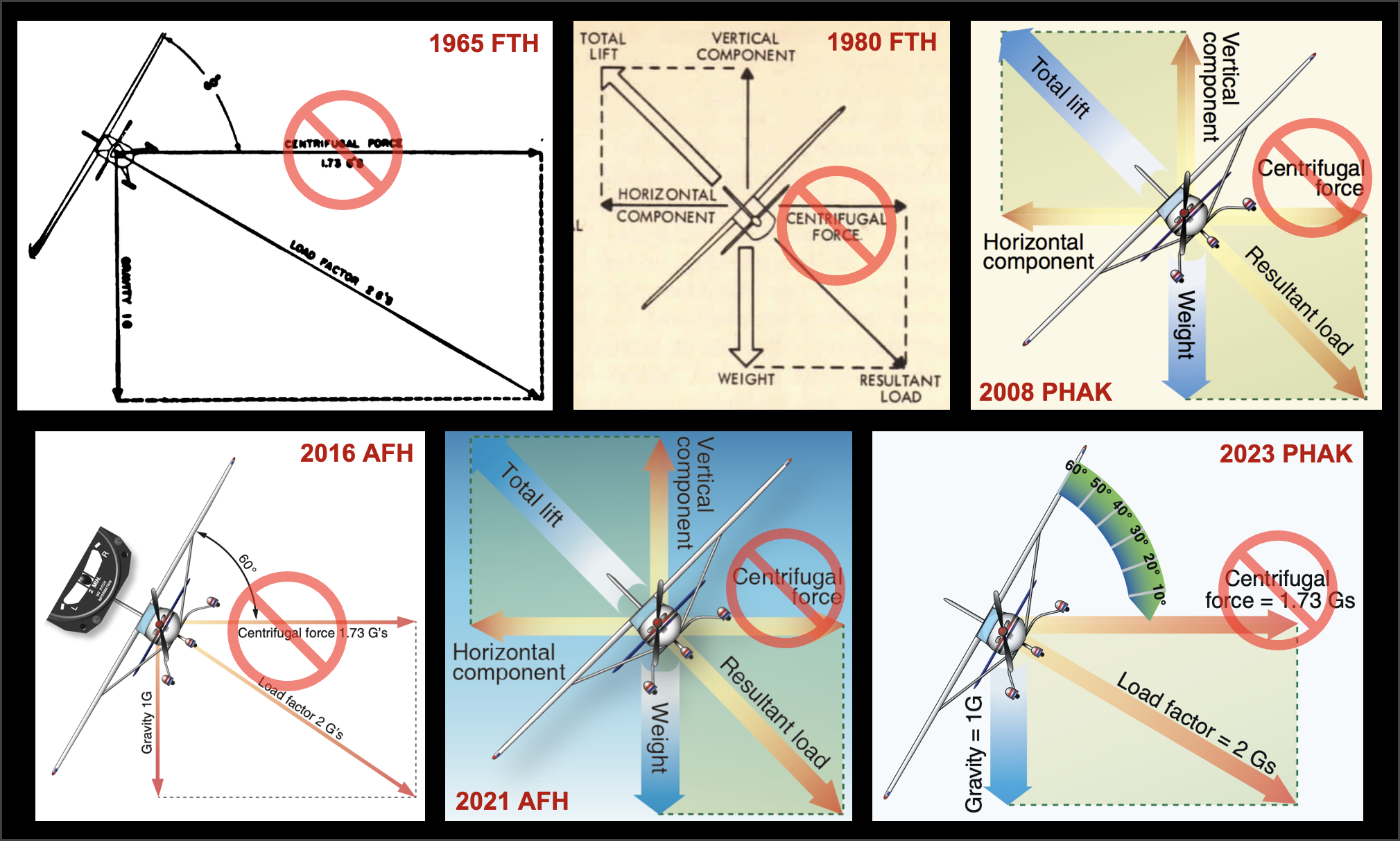

It’s hard to create good training content. Mistakes happen. Once identified, the mistakes can be fixed. But spreading myths and inaccuracies confuses the learning process. A long-standing example is the notion of centrifugal force in level turns. Pilot-physicist John T. Lowry notes, “there is no centrifugal force or even centrifugal pseudoforce acting on the turning airplane.”[10]

Nitpicky? The problem is this enduring error leads to odd and contradictory information. Consider these statements:

“The load factor is the vector addition of gravity and centrifugal force.”[11] Yet the same handbook defines load factor thus: “The ratio of the load supported by the airplane’s wings to the actual weight of the aircraft.”[12] This points to the classic expression, G-load = L/W. It has nothing to do with centrifugal force.

When turning, the handbook says, “the pilot is forced downward into the seat due to the resultant load factor.”[13] But the increased load factor doesn’t happen to the pilot. It happens because of the pilot. The pilot pulls the elevator control aft. That increases the G-load. The flightpath curves. The pilot is pressed into the seat.

FAA handbooks are intended to teach and inform. That’s a noble purpose. But as the above examples show, even these handbooks aren’t always reliable. So, how are you supposed to know what’s relevant and what isn’t? What’s accurate and what isn’t?

A good instructor might be able to help. But as a learner, you need to be proactive, too. Read different sources. Attend seminars. Apply critical thinking. Keep training. Keep asking questions. If something is confusing, get it cleared up.

Also, if you find something that needs to be changed in an FAA handbook, email AFS630Comments@faa.gov. Improvements in the content will benefit everyone.

[1] Kaitlyn Van Kampen, “The CRAAP Test,” The University of Chicago Library, https://guides.lib.uchicago.edu/c.php?g=1241077&p=9082343.

[2] H. Barber, Aerobatics, 1918, 5.

[3] FAA, “Aviation Instructor’s Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-9A, 2020, 3-37.

[4] Major Harley E. Barnhart, Modern Airmanship (edited by Van Sickle), 1957, 284.

[5] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, 1-2.

[6] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, 4-1–4-19.

[7] CAA, Flight Instruction Manual, CAA Technical Manual No. 100, April 1951, 116.

[8] Search for “oblique” in the current “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021.

[9] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, 3-2.

[10] John T. Lowry, Performance of Light Aircraft, AIAA, 1999, 245.

[11] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, 10-2.

[12] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, G-10.

[13] FAA, “Airplane Flying Handbook,” FAA-H-8083-3C, 2021, 3-3.

>> This post was written by a human <<

Sign up to receive an email whenever Rich Stowell publishes content