Optimising Student Pilot Development with the Ecological Dynamics Model

by Kristy How

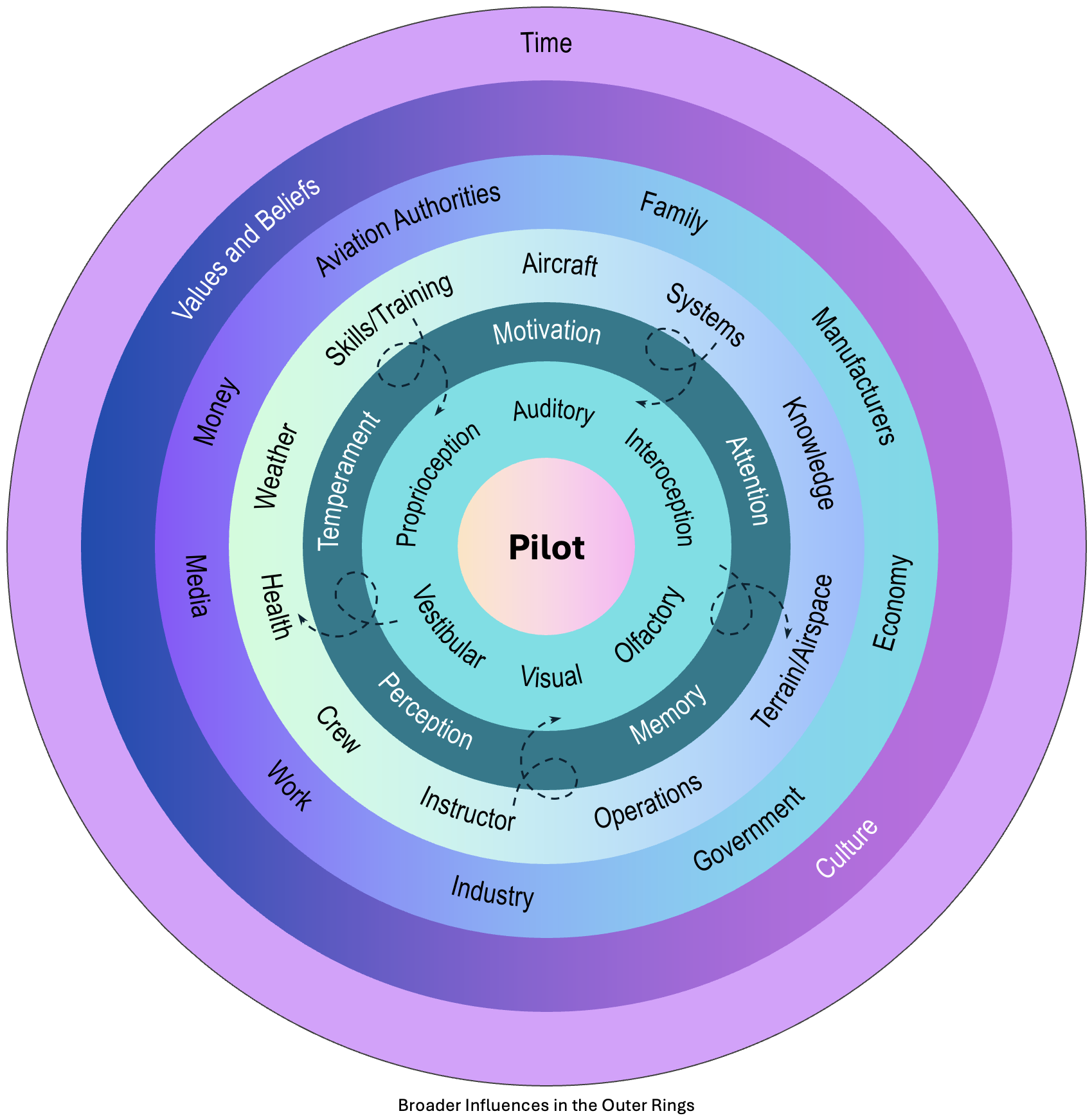

Learning to fly is more than just controlling an aeroplane or memorising procedures. It involves understanding the many different factors that affect a pilot’s training and decision-making in the air. The ecological dynamics model (EDM) helps explain this by showing how everything from the weather to the pilot’s own stress levels affects performance.

The original model was designed by educational theorist Urie Bronfenbrenner. He was researching how human development occurs within different systems. This model can be adapted to pilot training and flying in general. It can be used to demonstrate how various factors influence pilot performance in the cockpit. It reinforces that we should always consider the student pilot at the centre of a complex system.

Through a series of rings radiating outward, EDM can be used to explain the factors at play in flight training. This has implications for how we think about many concepts including student-centred learning, threat and error management and scenario-based training.

The First Ring: The Pilot's Inner Response

At the centre of the model is the pilot and their internal systems. These include how the body reacts to stress, movement, and changes in balance. For example, in steep turns, a pilot’s sense of balance (the vestibular system) can become confused, which might lead to disorientation. Training that helps pilots recognise and manage these internal responses is crucial, especially during emergency situations when stress is high.

The Second Ring: The Psychological Space

Between the pilot and the external world is the psychological space. It offers a simplified reminder of a complex psychological system. Arrows added to the model here show that this ring serves as a connecting layer with interactions in all directions.

The Third Ring: The Immediate Environment

Moving outward from the pilot is the first ring of external influences. It includes factors like the instructor, the aeroplane, and training materials. The relationship between the student and instructor is essential. A good instructor adapts their teaching to suit the student. The aeroplane itself is also a key factor. Each aeroplane behaves differently, and students need to learn how to handle different models in a variety of conditions. Clear and simple training materials also make it easier for students to understand complex concepts.

The third ring also has some variable forces such as weather and health. It is easy to change instructors or buy a new textbook. The weather and our health are more difficult to control. A flight over a quiet rural area requires a different level of focus compared to navigating busy airspace near a large airport. These rings show us why it is important to move beyond simply following checklists or memorising steps to being good decision makers.

The Outer Rings: Broader Influences

The outer layers of the model include broader influences like culture, media, and economics. These might not seem directly connected to flight, but they play a role in shaping a pilot’s mindset. For example, cultural attitudes towards safety can affect how a pilot approaches risk. Media coverage of aviation accidents can make pilots more cautious or anxious.

Economic factors also play a role. The cost of flight training can limit how much practice time a student gets, which can affect their development. These broader influences help explain how pilots think about flying and their long-term goals, whether for a career or recreation.

The concept of time is shown as the outer ring, and has an effect across all the rings. Together, the factors in this model form the foundation for effective learning.

The Value of Context: Moving from Rote Learning to Correlation

EDM highlights the importance of context in training. In flight training, moving beyond rote learning is essential. The model justifies the shift towards correlation—where pilots not only know what to do, but also understand why they are doing it and know how to apply it to new situations. This is why scenario-based training is so important.

In scenario-based training, students are placed in realistic situations where they must apply their skills in context. For example, rather than simply learning a climbing turn, the student must eventually learn how to choose the right kind of climbing turn configuration to safely depart a mountainous area. This type of training builds a deeper understanding and helps pilots make better decisions in real-life situations.

It also aligns with the threat and error management (TEM) approach, which encourages pilots to recognise and manage risks before they become problems. By focusing on context, pilots learn to think critically and adapt to the complexity of flying. By teaching in context, instructors move beyond theories and principles to make deeper learning connections that stick!

Why Decision-Making Matters

One of the key lessons from EDM is that pilots need more than memorised procedures. Rote learning can’t cover all the possible situations pilots will face in the air. Instead, they need a solid decision-making process. TEM is a framework that helps pilots identify potential risks and manage them before they become bigger issues.

For instance, a pilot dealing with unexpected turbulence and high amounts of air traffic could easily become overwhelmed. TEM helps pilots prioritise actions and stay focused, even when there are multiple challenges at once. This makes them better equipped to handle high-pressure situations and make quick, effective decisions.

Post-Flight Reflection: Using the Model to Review Performance

EDM has potential as a debriefing tool. It allows instructors and students to review how the pilot interacted with each layer of the model. For example, they might use it as a visual aid to assess how well the pilot engaged across the various levels. At the first inner ring, how well did the pilot manage the vestibular sensations during instrument flight. At the second ring, did they keep attention on vital tasks when offered a distraction. Further out, how did they manage aircraft limitations and respond to regulatory requirements. Again, this elevates instruction beyond concepts and into correlation. By reflecting on these elements, pilots can learn what went well and where they can improve, making future flights safer and more effective.

Conclusion

The ecological dynamics model (EDM) offers a comprehensive framework for flight training. It emphasises the importance of context and highlights how scenario-based training can advance pilots from rote learning to deeper, correlation-level understanding. By considering factors like internal reactions, environmental influences, weather, and culture, this model provides a holistic approach to developing skilled and adaptable pilots.

With the model, a complex and interwoven system of flight training is easier to visualise and communicate with instructors and student pilots. It is hoped the diagram can serve as both a catalyst and a tool for moving flight training beyond rote learning.

____________________________________________________________________________________

>> This post was written by a human <<

Sign up to receive an email whenever Kristy How publishes content